War poses everything in stark terms and thus puts all tendencies to the test. The war in Ukraine has led to a series of splits within the communist parties in several countries, as well as provoking divisions among them. In order to go forward it is necessary to return to genuine Leninist policies, on this and on all questions.

As soon as the war in Ukraine started, communist parties around the world took wildly different positions. On the right wing of the movement, several parties adopted a position of more or less open support for the ruling class of their own country and western imperialism. A particularly hypocritical example of this is the position of the Spanish Communist Party (PCE). The PCE is part of a Spanish coalition government with the Socialist Party (PSOE). Spain’s vice-president Yolanda Díaz and Minister Alberto Garzón are party members, and the PCE general secretary is also a secretary of state.

This government is firmly committed to NATO imperialism and has sent weapons and aid to Ukraine. But at the same time, the PCE issues statements demanding the disbandment of NATO and rejecting the war in Ukraine. Even its purely verbal so-called ‘opposition’ to NATO imperialism, is couched in terms of “peace” in the abstract, and defence of “international institutions” and the “rule of international law”.

A similar position was taken by the French Communist Party (PCF), which condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as being “against international law” and in breach of “international treaties”. In the same vein, the PCF upholds “France’s strategic independence”, which is the phrase under which the French ruling class advances its pretence to play an independent role in the world arena. Furthermore, while calling for “peace”, the PCF fully supports western imperialist sanctions on Russia, as if in some way economic sanctions are not also a part of the actual war. Their whole position is one of tail-ending the French bourgeoisie, which in the early days of the war was also calling for “peace negotiations” in an attempt to strike a somewhat independent position from that of US imperialism.

A large number of so-called communist parties, having abandoned Leninism a long time ago, are mesmerised by the idea of ‘peace’ in the abstract and of ‘the international institutions’, chiefly the United Nations.

This is far removed from Lenin’s position towards imperialist war. Lenin insisted that communists are not pacifists as there are wars we consider to be justified: wars of national liberation, against imperialism and revolutionary wars. Since war is the consequence of imperialism, the only consistent way to fight against war is to fight imperialism and the capitalist system from which it arises. Lenin’s slogan during the First World War was not that of “peace,” but rather, “turn the war into a civil war”. That is to say, he called for workers to fight their own ruling class. He explained that the war would eventually end, but that an imperialist ‘peace’ would be just the preparatory period for further wars later on. Therefore, Lenin insisted, the only way to achieve genuine peace was to struggle for socialism.

As for ‘international institutions’, Lenin and the Bolsheviks were scathing in their rejection of the United Nations’ predecessor, the League of Nations, which they described as a “thieves’ kitchen” – that is, a place where different imperialist powers came to share out their loot.

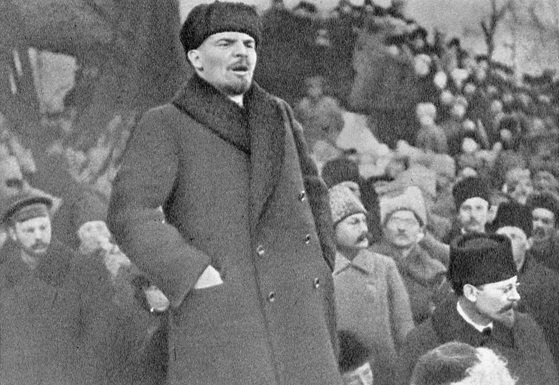

Lenin insisted that communists are not pacifists / Image: public domain

Lenin insisted that communists are not pacifists / Image: public domain

Lenin considered this point so important that he included rejection of the League of Nations in the famous 21 conditions for membership of the Communist International. These were meant to cleanse the new organisation of unworthy opportunist elements, which had joined under the pressure of the rank and file: “without the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism, no international arbitration courts, no talk about a reduction of armaments, no ‘democratic’ reorganisation of the League of Nations will save mankind from new imperialist wars.”

The position of revolutionary Marxists in the First World War (they did not adopt the name ‘communist’ until after the war) was summed up in Karl Liebknecht’s dictum, “the main enemy of the working class is at home”.

This basic internationalist principle has been abandoned by many communist parties around the world, not only in those countries that are part of NATO or support US imperialism, but also on the other side of the war. Thus, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) has also taken a shameful chauvinist position, uncritically defending Putin and the war he is waging in the interest of the Russian ruling class.

Split at the Havana International Meeting of Communist and Workers’ Parties

This abject capitulation led to an open conflict at the 22nd International Meeting of Communist and Workers’ Parties (IMCWP), which took place in Havana, Cuba on 27-29 October 2022. The IMCWP is an annual conference, which was initiated by the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) back in 1998. Communist parties from around the world meet to discuss and the conference usually ends with a joint statement, which is arrived at by consensus, rather than voted upon after a debate.

This time it was different. While a joint statement was produced, it did not deal with the war in Ukraine, which was only mentioned in passing. The statement ended with the words: “United in the struggle against imperialism and capitalism!” But the nearly 60 parties participating were very far from being united on this question.

The meeting was in fact, sharply divided over the Ukraine war. In its intervention, the Russian Communist Workers’ Party (RCWP) argued that Russia’s war was “just and defensive”, and that the task of Communists was to support the Russian bourgeois state as it was fighting “to suppress fascism and assist the national liberation struggle in Ukraine”.

The CPRF, for their part, were correctly accused by the KKE of supporting Putin and his United Russia party, and retorted that, in fact, it was Putin who was supporting them! “It is not that the CPRF ‘has shown solidarity with United Russia and President Putin,’ but [United Russia and President Putin], owing to historical imperatives, have to follow the path the CPRF has persistently called for over three decades.”

Two separate declarations were therefore issued on the war. One was proposed by the Russian Communist Workers’ Party (RCWP), the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF), and the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU), which basically repeated the arguments of the Russian ruling class in justification for their intervention in Ukraine; whilst peppering these justifications with a fair dose of “Communist”, “proletarian” and “anti-fascist” seasoning. It contains no attempt to analyse the war aims of the Russian capitalist class, nor does it contain a single word of criticism of Putin and his reactionary capitalist regime. That this was proposed by two parties calling themselves ‘Communist’ from Russia is an utterly scandalous capitulation to social-chauvinism. This statement was signed by 23 IMCWP participant parties, and another 12 organisations not participating in the meeting.

In response, a second counter-declaration was issued, signed by 24 parties participating in the IMCWP, notably including the KKE, plus another four. This starts by describing the war as a capitalist war on both sides. It also denies any claim that the Russian government has anything to do with the anti-fascist struggle or with pro-Soviet sentiment, correctly pointing out that Russia is a capitalist country, something which some, incredibly, do not seem to understand:

“The Russian Federation, being a bourgeois state, is only nominally, in the framework of bourgeois law, the inheritor of the USSR, while it has nothing in common with the USSR either in its base or superstructure. During the 30 years of ‘independence’ of the Russian Federation, financial and monopolistic capital was created; industry, education, and health care sectors were systematically destroyed; unemployment increased, and the gap between the rich and the poor grew, labour rights and democratic freedoms were eliminated.”

This second resolution also correctly criticises “the militarisation of Ukraine, promotion of an extremely reactionary nationalist ideology, incitement of inter-ethnic hatred, creation of nationalist militant groups,” as well as the suppression of labour and political rights. But perhaps the most interesting part of the resolution is point five, which explains how to put an end to the war in Ukraine:

“We are certain that it is only the Ukrainian working class united with the Russian proletariat and supported by the workers of the world that are able to stop the imperialist slaughter. Ukraine’s, Russia’s and world bourgeoisie mobilised and armed workers. It is necessary that these armaments be aimed at the governments of war, to convert the imperialist war between the peoples into a civil war between classes. It is only this that will enable the working class to put an end to imperialism as a source of wars and form bodies of workers’ power, as well as transform the combating states in the interests of working people.”

This is absolutely correct, and is in fact a repetition of the arguments made by Lenin during the First World War.

The Russian Communist Workers’ Party (RCWP) argued that Russia’s war was “just and defensive” / Image: AFU StratCom, Wikimedia Commons

The Russian Communist Workers’ Party (RCWP) argued that Russia’s war was “just and defensive” / Image: AFU StratCom, Wikimedia Commons

It is remarkable, however, that in the Spanish version of the statement, which has also been published on the official IMCWP site, this whole section is missing, being replaced instead by talk of “immediate peace negotiations”, a “ceasefire”, the “investigation of war crimes committed by all sides in the conflict” (without saying who is going to carry out such an investigation), etc. This is at odds with the English version, which correctly explains that it is the task of the working class to fight imperialism and war.

The second, internationalist, resolution then launches a correct and sharp head-on attack on the supporters of the first pro-Russian resolution:

“It is shameful and criminal for communists all over the world to trail behind the governments of bourgeois countries and work for the interests of their national bourgeoisie, to support one or another bloc of bourgeois countries. Our immutable task is to help workers all over the world realise that imperialist wars do not lead to the emancipation of labour, on the contrary, they enslave it even more; that in the imperialist conflict the working class has no allies among the ruling circles, only enemies; that their friends are only the proletarians, no matter what nationality they may be.”

We fully agree with this. There are of course some criticisms that could be made of the internationalist resolution. The analysis of the causes and character of the war in the first part is very schematic and underdeveloped. It says nothing about the role of US imperialism and its provocative eastward expansion of NATO over 30 years; it does not deal with the reactionary Maidan movement of 2014 and the regime that it established, etc. Many of these points are explained in the Havana meeting joint statement, but the internationalist resolution would have been strengthened by including them.

How not to build an international

This is symptomatic of a major problem in the method used to build the IMCWP. The fact that parties that are completely at odds, can sign a joint declaration avoiding the issues in dispute, even if these are central to the world situation, and then produce two additional statements with opposing views, makes a farce of the idea of building an international Communist organisation. In fact, the IMCWP is based on diplomacy, rather than a frank struggle of ideas.

It should also be noted that there were a number of parties that signed the final statement whilst having a purely bourgeois pacifist position, of trust in the “international institutions”, and even some (like the PCE in Spain) that are participants in governments that are part of NATO and are sending weapons and funding to Ukraine. The PCE and other parties sharing a similar position are then allowed to sign the Havana IMCWP joint statement talking about the struggle for socialism, the interests of the world proletariat, and the promotion of Marxism and Leninism, while sitting in a pro-imperialist government.

Even amongst those organisations that signed the second, more principled statement, there is a great deal of hypocrisy. How else can you explain the fact that the South African Communist Party (SACP) – which has had a two-stage policy for decades and has been part of the ANC capitalist government for nearly 30 years (a government which ordered the security forces to open fire on striking miners at Marikana, in defence of the interests of the multinational mine-owners) – is allowed to put its name to a resolution which says “it is shameful and criminal for communists all over the world to trail behind the governments of bourgeois countries and work for the interests of their national bourgeoisie”?

This would have been unthinkable in Lenin’s Communist International. There were many sharp debates while Lenin was alive, and there were occasions in which Lenin himself was in a minority. But he never thought of saying, “well, we can have a joint statement avoiding the polemical questions, and then each faction can have their own separate statements about the issues we disagree with.” Such a procedure makes a mockery of the very idea of a Communist international, which should be based on democratic centralist principles, not on ‘unanimity’ and certainly not on ‘consensus’.

The sharpness of the split that took place at the Havana meeting is the result of the war in Ukraine, which brought crucial issues to the fore, but also of the method of papering over differences used before in these IMCWP meetings.

There were also a number of parties present that do not seem to have signed either statement on the war in Ukraine, including the Communist Party of Britain, the Communist Party of France, the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and the Communist Party of Cuba, among others.

The dispute at the Havana meeting continued with a series of attacks by participating parties on each other, and public statements by the CPRF, the RCWP, the KKE, etc. The split revealed at the Havana meeting had serious consequences for several of the parties involved.

It led to a split in the RCWP, particularly affecting its youth wing and its trade union front. The party was reduced to a rump. The social-chauvinist position the RCWP leadership adopted towards the war in Ukraine, in direct contradiction to its claim to stand for Marxist and Leninist principles, has destroyed it. Previously, the leadership could claim to stand to the left of the CPRF, but now they have adopted exactly the same chauvinist position. The hypocrisy and double standards of the party leadership in public and towards its own members were finally laid bare.

The split amongst the IMCWP participants has now led to the decision, taken by the KKE, to disband the European Communist Initiative, the European equivalent of the IMCWP, and will probably lead to the dissolution of the IMCWP itself at its forthcoming meeting in Turkey. Lessons must be drawn. An international can only be built on the basis of political clarification and principled agreement, not diplomacy and empty speechifying.

The so-called Anti-imperialist Platform

The split amongst the Communist parties that came to the fore at the Havana meeting had been anticipated by the formation of the so-called World Anti-imperialist Platform (WAP), promoted by the People’s Democracy Party of Korea and with the participation of several of the IMCWP parties. The organisation of the Platform seems to have a lot of resources, and has organised five international meetings in the space of one year with all expenses paid (two in Paris, one in Seoul, one in Belgrade and one in Caracas).

The political line of this Platform is very clearly stated in its founding ‘Paris Declaration’. The main points are: “there is no economic data to justify characterising China or Russia as imperialist”; “that Russia, China and the DPRK are the targets of imperialist aggression because they represent a serious threat to the imperialists’ world hegemony”; “We must challenge the misleading and dangerous practice of certain forces calling themselves ‘communist’ and ‘socialist’ who have declared the war in Ukraine to be an ‘inter imperialist’ conflict in which both sides are equally aggressive and to blame”, and furthermore: “Russia and China in particular are able not only to defend themselves against imperialist bullying but also to help small or economically weak developing countries stand up for themselves and break free of imperialist colonisation and debt slavery.” And as a consequence of this, the Platform argues that the people “should be educated” on these questions and anti-imperialists should stand for the victory of Russia and China: “Victory to the forces of national-liberation and anti-imperialist resistance!”

The PSUV has used the state apparatus to launch an attack on the Communist Party of Venezuela / Image: Nicolás Maduro, Twitter

The PSUV has used the state apparatus to launch an attack on the Communist Party of Venezuela / Image: Nicolás Maduro, Twitter

The groups involved in this Platform are a strange amalgam of small Maoist sects, Titoist organisations, a few Italian fringe groupings, etc. The RCWP has typically played cat and mouse with it. While participating in the meetings and publicly defending the main ideas of the Platform, it has refrained from actually signing the declaration in an attempt to cover itself up.

As well as some parties, which can be considered left wing in one way or another, there are also some openly reactionary organisations in the Platform. Among them is Vanguardia Española, a Spanish chauvinist sect, which mixes support for Spanish colonisation of America with references to Marxism. This is not too surprising. Once you abandon a class point of view and adopt a chauvinist position, everything is possible. In fact, one of the triggers for the split in the RCWP was the move of its leadership towards joint work with Limonov’s group, the openly fascist National Bolshevik Party of Russia. Meanwhile, the ‘Communist’ Party (Italy) of Marco Rizzo (also part of the WAP) had an electoral alliance with people who had been linked to the fascist party Forza Nuova, all in the name of “defending national sovereignty”.

Also part of the Platform is the Venezuelan ruling party, the PSUV, which in recent years has carried out a policy contrary to that which led to all the gains and advances of the Bolivarian revolution under Chavez. Its policy has involved privatising factories that were previously nationalised; taking land from the peasants to give it back to the old landowners; jailing trade union activists, and implementing a brutal monetarist package to make the workers pay the price for the capitalist crisis.

More than this, in recent months, the PSUV has used the state apparatus to launch an attack on the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV), which has reached the point of the Supreme Court removing the PCV’s elected leadership and replacing it with an ad hoc junta made up of non-party members. This was done in order to take over the party’s electoral registration.

In terms of size, the so-called WAP is quite irrelevant. But the positions it advances are more widespread, particularly the idea that somehow China and Russia are anti-imperialist and play a progressive role in world relations.

Are Russia and China anti-imperialist?

In Russia, capitalism was restored after 1991 by the degenerate leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union / Image: Kremlin.ru

In Russia, capitalism was restored after 1991 by the degenerate leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union / Image: Kremlin.ru

We have dealt with these questions in detail elsewhere (see: Imperialism today and the character of Russia and China) but it should be clear to everyone that both countries are capitalist. In Russia, capitalism was restored after 1991 by the degenerate leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union – a bureaucratic layer that was not content with deriving enormous privileges from the state-owned planned economy, and instead wanted to convert itself into the private owners of the means of production. This they did through the wholesale looting of state property in a reactionary process, which led to a brutal collapse of living and cultural standards, throwing the working class back decades.

After a period in which the new capitalist ruling class was completely under the domination of western imperialism (represented by the Yeltsin years), it then gained confidence and started asserting its own interests, first in the regional (Georgia, Ukraine, Caucasus), and then, although to a lesser extent, on the world arena (Syria, Africa).

In China, the process of capitalist restoration took place over a protracted period of time with the ‘Communist’ Party remaining firmly in power. Now, however, it serves completely different property relations: no longer those of the planned economy but of a capitalist economy. Initially, this transition occurred by allowing foreign capital in. But progressively, the Chinese capitalist class started to assert its own separate interests, under the protection of the Chinese state. Increasingly, China has become an imperialist power, although relatively weak compared to US imperialism. It exports capital, which it invests abroad in order to secure sources of energy and raw materials, to protect its trade routes, and to control fields of investment and markets for its exports. In the process, it has come into conflict with US imperialism, the dominant world power. This is the meaning of the trade and military tensions between the two.

However, we need to have a sense of proportion. US imperialism is still the dominant power in the world due to its economic weight and control of the international financial system. Its military might is derived from its economic power and the superior productivity of labour it is capable of achieving. Yes, US imperialism is in relative decline, but only relative decline. Yes, China and to a lesser extent Russia are rising imperialist powers, but they are still much weaker than the US.

The task of communists is not to support one bloc against the other, but rather to defend the interests of the working class everywhere against those of the ruling class, primarily our own ruling class at home.

The split in the Brazilian Communist Party

The most politically interesting fallout of the conflict amongst the different Communist parties on the war in Ukraine is the recent split in the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB), which was triggered directly by the participation of its leadership in these meetings of the World Anti-Imperialist Platform, a move that was against party policy as agreed at its most recent congress.

Within the PCB, a left-wing opposition coalesced against the policy of supporting the interests of the capitalist ruling class of China and Russia. The former general secretary of the PCB, Ivan Pinheiro, was critical of the party’s participation in the WAP meetings and the statements made at them by the party leadership. After being bureaucratically blocked from expressing his critical views internally, he decided to issue a public document in June.

The leadership of the PCB responded to the growing support for the left opposition around Pinheiro, particularly strong amongst the party’s youth, by resorting to bureaucratic measures and expulsions. The left opposition demanded that the party congress, long overdue, should be convened so that all differences could be debated democratically. This was the last thing the clique in the leadership wanted, as it feared it would become a minority if there was a democratic debate in the ranks. Things came to a head at the end of July when the leadership decided to expel five CC members, including Pinheiro himself on spurious grounds.

Rather than becoming demoralised, those expelled mounted a counter-offensive, launching a Manifesto for the Revolutionary Reconstruction of the PCB. As the weeks went by, an increasing number of party, local and regional organisations, cells and organisations of the youth (UJC) declared their support for the left opposition and came out in favour of the PCB RR. As Ivan Pinheiro explains:

Within the PCB, a left-wing opposition coalesced against the policy of supporting the interests of the capitalist ruling class of China and Russia / Image: Пресс служба Президента России, Wikimedia Commons

Within the PCB, a left-wing opposition coalesced against the policy of supporting the interests of the capitalist ruling class of China and Russia / Image: Пресс служба Президента России, Wikimedia Commons

“I believe that the outbreak of the war in Ukraine was the fuse that sparked this intense polarisation… it has forced us to debate issues that many of us were reluctant to face up to, including the character of the Chinese state and the relevance of imperialism, the class illusion of so-called multipolarity, the role of communists in the face of a war between national bourgeoisies that turn their proletariats into cannon fodder and which is inseparable from inter-imperialist disputes.”

The right-wing shift of the leadership of the PCB was not limited to international affairs. As Pinheiro’s left opposition pointed out, it went hand in hand with a growing adaptation to bourgeois democracy and the government of Lula, which is one of open class collaboration. The fact that the PCB receives electoral state funding for political parties helps the party bureaucracy gain a degree of independence from the party ranks, thus solidifying its reformist tendencies.

We welcome the struggle waged by the expelled left opposition of the PCB and their efforts of revolutionary reconstruction. We find ourselves in very close agreement with the comrades on key questions of international and national politics, and this sets the ground for fraternal collaboration, as we collaborated a decade ago when Pinheiro was the general secretary of the party. That collaboration extended to the question of Ukraine and the struggle against the Maidan regime in 2014. Of course, there are differences between our organisations – inevitably – but we agree on one fundamental question: we stand firmly on the principle of proletarian class struggle, against any collaboration with the bourgeoisie and any form of ‘stageism’, which puts off the socialist revolution to a far off, distant future.

A rebellion of the youth: back to Lenin!

The dispute over the position towards the war in Ukraine was not the only element in the crisis of the PCB. There is another element, which is common to the crisis in a number of other Communist parties around the world.

In the recent period, and particularly during the pandemic and the lockdown, a layer of youth joined the party, attracted by its communist name. These were fresh, new layers, imbued with a revolutionary spirit, and they soon clashed with the leadership, which was unable to offer them any inspiration or political education. Some of the new youth they recruited became quite popular on different social media platforms for their defence of the ideas of communism. Their prominence was seen as a threat to the party leadership, and so they became the first ones to be hit by bureaucratic measures. The use of administrative measures to solve political debates is a clear sign of a leadership which has no trust in its own ideas.

This phenomenon – the influx of youth into communist parties, attracted by the name and symbols, their rejection of the reformist policies and parliamentary cretinism of the leadership and of the use of bureaucratic measures to suppress them – is quite widespread. Rizzo’s ‘Communist’ Party in Italy lost its youth organisation. The Connolly Youth Movement (CYM) broke with the Communist Party of Ireland at the beginning of 2021, after a series of splits and conflicts. In Spain the PCE has just expelled the whole leadership of its youth movement, UJCE, and appointed an ad hoc leadership, after the youth developed a strong criticism of the reformism of the PCE leadership and were silenced at the last party congress. The list goes on.

A cursory examination of Stalin’s policies would reveal that they represent a fundamental break with Lenin and Leninism / Image: public domain

A cursory examination of Stalin’s policies would reveal that they represent a fundamental break with Lenin and Leninism / Image: public domain

In several of these cases, the new, young, radical elements have gravitated towards the figure of Stalin as a reaction against the reformism of the leadership of the party. This is understandable, but wrong.

A cursory examination of Stalin’s policies would reveal that they represent a fundamental break with Lenin and Leninism. Where Lenin firmly defended a strategy of no confidence in bourgeois liberals and the need for the working class to take power, Stalin brought back the Menshevik ‘two stage’ theory of alliance with the ‘progressive bourgeoisie’, which led to disaster in China, Spain and elsewhere. Where Lenin opposed “international institutions” like the League of Nations, which he described as a “thieves’ kitchen”, Stalin brought the USSR into the League of Nations in 1934. Where Lenin advocated proletarian internationalism, Stalin courted the different imperialist powers, and then disbanded the Communist International in May 1943 as a gesture of goodwill.

On the question of methods of party democracy and democratic centralism, we have to say that in many cases, these youth have been on the receiving end of bureaucratic methods, which are typical of Stalinism and have nothing to do with the clean banner of Leninist democratic centralism. While Lenin was alive, debate thrived within the Communist International and the Russian party on many different questions: the Brest-Litovsk negotiations, the trade union question, the New Economic Policy, the United Front, participation in parliament and trade unions, etc. That made the party and the International stronger, not the opposite.

We ask those comrades who are members of communist parties, and who have rightly come into opposition, to examine these questions carefully as they are not of merely historical interest. On the contrary, they are extremely relevant to the discussions taking place today among Communist parties about imperialism, the character of Russia and China, the role of the BRICS, and the idea of a so-called “multipolar” world.

Of course, some will say: “but you are Trotskyists!” And so we are. We defend the ideas and traditions of Trotsky, but we think these are not different from the ideas and traditions of Lenin. On all the aforementioned questions (working-class independence, opposing collaboration with the bourgeoisie, proletarian internationalism, and a democratic centralist form of organisation) there was no difference between Lenin and Trotsky after 1917.

It is true that many who call themselves ‘Trotskyists’ have in fact capitulated to the ruling class, and in relation to the war in Ukraine have adopted a treacherous pro-imperialist position. This is the case for instance with the so-called Fourth International, whose scandalous slogan is “sanctions on Russia, weapons for Ukraine”. They are de facto on the same side as NATO imperialism, i.e. their own ruling class, in this war.

This has nothing to do with the genuine ideas of Trotsky and is the result of having abandoned a class point of view, in the same way that those ‘Communist’ parties which support their own imperialist ruling class have nothing to do with Lenin or Leninism, regardless of how they claim to define themselves.

We are firmly convinced that on all of these questions, which are crucial for Communists today, it is necessary to break with reformism, chauvinism and adopt a principled working-class point of view. That is, it is necessary to go back to Lenin. In this way, the basis can be laid for the rebuilding of a genuine and revolutionary Communist international which can only be created through political struggle and not through diplomatic combinations.

https://assets.contropiano.org/img/2023/10/Palestina-insurrezione.jpg 678w» alt=»» width=»300″ height=»201″ class=»size-medium wp-image-164973 alignright» decoding=»async» loading=»lazy» />

https://assets.contropiano.org/img/2023/10/Palestina-insurrezione.jpg 678w» alt=»» width=»300″ height=»201″ class=»size-medium wp-image-164973 alignright» decoding=»async» loading=»lazy» />